This is the thirty-first installment in a series of articles tracing the complete history of superheroes in film and television, from the first superhero serial all the way to the current Marvel and DC cinematic universes. For the previous installment click here, for the first installment click here.

After the controversy surrounding Tim Burton’s “Batman Returns,” and numerous boycotts and protests from parents groups claiming the film was “unsuitable for children,” Warner Bros. decided to ask Burton not to direct the third, but to stay on as producer. Burton – who had originally been hesitant to return for a second – was excited at prospect of doing a third, but he reluctantly agreed provided he could hire his own replacement. The studio agreed.

Tim Burton had planned to hire a director who had a similar gothic style to his own and who was known for making dark pictures. He chose “The Lost Boys” director Joel Schumacher for the job. This would be a decision that would forever go down in infamy, but to be honest the next two Batman films would have been the same no matter who was directing, and to lay the blame solely at the feet of Joel Schumacher – which is often done – is unfair.

Whereas Burton had been given complete creative control over “Batman Returns,” the production of “Batman Forever” was mired in studio mandates to make up for what had been the perceived failures of the last film. The first of these mandates was that “Batman Forever” feature the character Robin, who had been left out of the last two pictures. The studio felt that Robin would add to the film’s appeal to children by offering them a character to identify with, which was the idea behind the original creation of the character in 1940.

When Tim Burton was asked not to return, Michael Keaton also decided that he would not be reprising his role as Batman. This left the production in need of a new caped crusader, and Joel Schumacher set about the daunting task of finding someone who could follow Keaton as the Dark Knight. A few days after Michael Keaton officially bowed out, Joel Schumacher cast Val Kilmer as the new Batman.

For Robin, Marlon Wayans had originally been cast and signed on to the film before Burton’s departure. Schumacher, wanting to keep a fidelity to the source material, made the decision to replace Wayans with a white actor. Leonardo DiCapprio was the first choice, but he turned the role down. Every actor between the age of 17 and 25 auditioned for the part. Among the future Hollywood stars to audition were Alan Cummings, Ewen McGregor, Jude Law and Mark Wahlberg. The part eventually went to Chris O’Donnell.

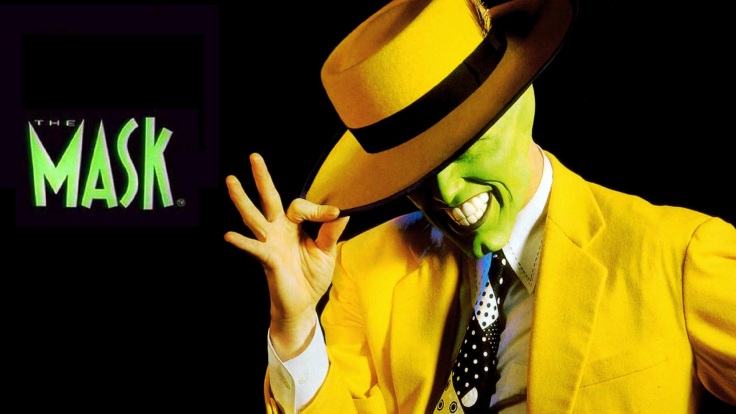

Michael Jackson campaigned for the role of the Riddler, but he was dismissed out of hand. Robin Williams was the first choice for the role, but he turned it down. During production of the first “Batman,” Robin Williams was used as bait to get Jack Nicholson to sign on as the Joker. Williams was never seriously considered for the part, but he was used as a bargaining chip to get Nicholson, and Williams didn’t appreciate that. Because of the animosity he held for Tim Burton for using him, he declined to appear as the Riddler. The role went to Jim Carrey, who played the part very much akin to Frank Gorshin’s portrayal in the 1966 television series.

In the original film, the character of Harvey Dent – in that movie Gotham City’s District Attorney, but destined to become the villain Two-Face – was played by Billy Dee Williams. Williams has said that he originally took the role of Harvey Dent in the hopes that he would one day get to play Two-Face, as he was familiar with the comic books. The same as with Robin, Schumacher was hesitant to stray from the source material. His first and only choice to play the role was Tommy Lee Jones – whom Schumacher had worked with on the John Grisham adaptation “The Client” – and because of this, Williams was never offered the opportunity to return. It is because of reasons like this that the Burton and Schumacher films are generally considered separate franchises, in spite of sharing very loose continuity.

While “Batman Forever” carried a decidedly lighter tone than the previous two, it was generally given favorable reviews by critics. Many critics praised the film for lightening its tone after the gothic romp that was “Batman Returns.” Among fans, the general consensus was that it wasn’t as good as the previous two, but it wasn’t terrible either. “Batman Forever” would also go on to earn almost $100 million more than its predecessor at the box office.

The success of “Batman Forever” – and yes, it was considered a success at the time – led to another sequel with Schumacher at the helm. Burton declined to returned as producer, because he disagreed with the direction Warner Bros. – not Joel Schumacher – took the last film in. The success of “Batman Forever,” unfortunately, also reinforced with Warner Bros. that their mandates had been the right direction in which to take the film. Because of this reinforcement, they decided to increase the mandates to absurd levels.

Joel Schumacher has been criticized for his use of the phrase, “Remember this is a cartoon,” when directing the actors. Schumacher did direct with this phrase, but it wasn’t because he personally didn’t take the material seriously. That was a mandate from the studio, that the films be made like a live action cartoon. Warner Bros. was also concerned that the film be able to translate itself to as many toys as possible. They even went so far as to allow the toy company to design and dictate how props and vehicles were to look. This is also why Batman, Robin and Batgirl go through at least two costume each. So they could make and sell toys.

Joel Schumacher’s insistence on fidelity to the source material did not, apparently, extend to the character of Batgirl. In the comics, Batgirl is Barbara Gordon, daughter of the police commissioner. In the film she became Barbara Wilson, great niece of Alfred Pennyworth, Bruce Wayne’s butler. Her mask was also changed from a full cowl – like Batman’s – to a domino mask, similar to what Robin wears. The full cowl can be seen briefly, but it’s quickly discarded for no apparent reason at all.

Val Kilmer did not return as Batman. While Kilmer and Schumacher’s stories conflict, they two men infamously clashed on the set of “Batman Forever” and neither probably wanted Kilmer to return. While Schumacher maintains that Kilmer was always welcome back, but was committed to “The Saint” and was unable to return, Kilmer claims he was never asked to return or even told there would be another movie. Kilmer claims he didn’t know there was going to be another film until he read that George Clooney had been cast as Batman.

In keeping with every Batman film apart from the first one, this “Batman and Robin” also employed two villains. Villains popular at the time, due to the popularity of “Batman: The Animated Series” were Mr. Freeze and Poison Ivy. Mr. Freeze was played by Arnold Schwarzenegger – presumably because Schwarzenegger is Austrian and Mr. Freeze is German – while Poison Ivy was played by Uma Thurman. As with the previous movie, both villains were played over-the-top.

Mr. Freeze’s backstory was taken directly from the animated series. Traditionally, Mr. Freeze was always just portrayed as a mutated thief. A street thug mutated in an accident while trying to escape Batman, and he blamed Batman for the accident. In the backstory created by Paul Dini for the animated series, however, Mr. Freeze was turned into a much more tragic character. While this was retained for the film, it wasn’t really used properly and just felt kind of shoehorned in.

“Batman and Robin” was a financial disaster and received very negative reviews. The general consensus had been that they went too far in the light-hearted and cartoony direction. Many compared it to the 1966 television series, and the comparison was not at all favorable. “Batman and Robin” killed the series, and cemented Schumacher’s reputation as the man who ruined Batman, a reputation he will probably never live down. Schumacher did want the opportunity to redeem himself, to direct a dark Batman in keeping with other films he’s directed, but Warner Bros. wouldn’t have it. Instead, it would take eight years for Batman to see new life.

If you enjoyed this article, feel free to like me on Facebook, follow me on Twitter and check out my column at TheBlaze.

References:

“Batman 3“. Entertainment Weekly. October 1, 1993.

Shadows of the Bat: The Cinematic Saga of the Dark Knight-Reinventing a Hero (DVD). Warner Bros. 2005.

Army Archerd (December 1, 1994). “Culkin kids ink with WMA”. Variety.

Jeff Gordinier (July 15, 1994). “Next at Batman“. Entertainment Weekly.

Judy Brennan (1994-06-03). “Batman Battles New Bat Villains”. Entertainment Weekly

Batman Heroes Profile: Harvey Dent (DVD). Batman Special Edition: Warner Bros. Home Video. 2005.

“Christopher Nolan: The Movies. The Memories.” Empire. July 2010.

“DiCaprio Interview”. Shortlist. 2010-07-15.

Whos Talking